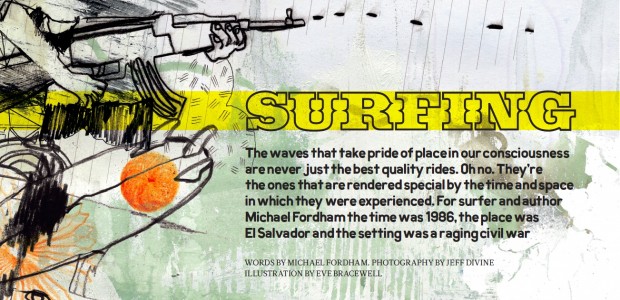

A trip to El Salvador in the 80s, and a testament to how evanescent ridden waves can crystallise into permanent form when they are loaded with personal significance.

When I recall waves that I have ridden I am left only with sensory fragments. It’s as if a series of fleeting moments are burnt onto my frontal lobes. Am I the only one who experiences it like this? In fact, in years of riding waves, I can only fully recall one whole ride in all it’s beautiful intensity. It wasn’t a particularly perfect, particularly epic wave. It’s what that time, that place and that particular moment meant to me that crystallises each second of itself into my specific eternity.

There was no way I could ignore the urge to go to El Salvador. I’d seen a piece on the place in a crumpled old edition of Tracks magazine, what was then a newsprint missive from Australia’s surf counterculture. It was in a pile of old magazines in a chartered Catamaran in which I was becalmed off the reef-fringed Whitsunday Islands in Queensland. The black and white pictures were artfully grainy and badly framed, but this only added to the mystery the piece evoked. La Libertad. The name meant freedom. There had been a civil war raging but the place was blessed with the perfect right-hand pointbreak. I was a naïve teenager on the road, learning to surf and learning to live. Such things were infused with an irresistible glamour. I should have known better.

I arrived in El Salvador a year later, in October 1986. The capital, San Salvador, was seething. The first thing we noticed was the absence of men. There were women everywhere. Males of marriageable age are either in the army or the various other government militias, or up in the hills with the guerrillas, or have simply ‘disappeared’. I’d been travelling with a cerveca-obsessed thirty three year old kneeboarder from Llantwit Major, Wales with a hairy, slightly paunchy belly but whose eyes were irritatingly blue. We’d hooked up on mainland Mexico and had gotten pummelled together by Puerto Escondido’s churning brew. Somehow, Phil and I had just clicked. I was a testosterone-jacked teenager, and he was strangely world-wise and able to attract the best looking women in town. I, all gangly and with hardly a hair on my chin, always ended up with Phil’s cast-offs (waves as well as girls). I’d mentioned my mission to surf La Libertad to Phil one Tequila-tainted night in Puerto and he’d muttered that he wouldn’t mind a bit of that himself. Everyone else on the Gringo trail had pulled a funny face when they I mentioned I was heading to Salvador. I’d found a kindred spirit.

Everyone else on the Gringo trail had pulled a funny face when they I mentioned I was heading to Salvador.

So there we were, a pair of six feet tail, fair-skinned gringos carrying surfboards in a land full of dark, stocky blokes strapped to the hilt with Armalites and 7.62 shells. The bus was set to arrive in San Salvador from Guatemala City just before the dusk curfew, but, grilled as we were by a succession of murderous looking men in psychedelic camo and mirrored shades, it took an age to get through border control. Night fell soon after we entered the country with our puny 14-day visas and we had to pull in to the nearest town to stay for the night. There was no power in the village, as the rebels were always, apparently, cutting supply. We drank twenty cent beers and were plied with tacos, and rice and beans and ate and drank surrounded by wide eyed kids and amused old men and women who hadn’t seen a gringo in years. “No hay problema aquí mi amigo. La guerra está para arriba en las colinas.” The man serving the beers reassured us that it was cool and that the war was confined to the hills. Problem was, it looked pretty hilly exactly where we were. The two dollar room in the back of the bar he showed us to stank of corn and donkey shit, but it didn’t matter. Only when we blew out the candles did we begin to make out the distant rattle of small-arms fire and the rhythmic thwump of mortar rounds. Phil and I stared through the gloom at one another and giggled like the bong-happy idiots we were.

Predictably, I dreamt of waves that night. In fact I was comfortable in the middle of majestic maraschino cherry-hued scene of languidly-peeling point waves when at six am the bus driver (who turned out to be our host’s brother in law) rattled the shutters. After some coffee and eggs and tortilla we hopped on the bus and in less than an hour we were trundling through the ruptured textures of San Salvador’s eastern environs. As soon as we hit the tarmac at the bus station we began to attract an unhealthy amount of attention. Pre-teen street hustlers elevated to status of mack-daddies because of the absence of the usual male hierarchy were bantering with us with a threatening sort of Spanglish and giving us the stink-eye. Senoras in floral dresses who hadn’t seen their husbands in years flirted with us and the younger girls giggled and ran and stared behind their schoolbooks. Negotiating a bus station in Central America can be interesting at the best of times, but this was in the middle of a chaotic armed struggle between a CIA-backed extreme right wing government and their masked death squads and an impoverished collective of leftist guerrillas whose figureheads were martyred priests. The smell of cordite in the air and the frenzied atmosphere on the street confirmed that getting out of dodge was definitely the best thing to do.

Predictably, I dreamt of waves that night. In fact I was comfortable in the middle of majestic maraschino cherry-hued scene of languidly-peeling point waves when at six am the bus driver (who turned out to be our host’s brother in law) rattled the shutters. After some coffee and eggs and tortilla we hopped on the bus and in less than an hour we were trundling through the ruptured textures of San Salvador’s eastern environs. As soon as we hit the tarmac at the bus station we began to attract an unhealthy amount of attention. Pre-teen street hustlers elevated to status of mack-daddies because of the absence of the usual male hierarchy were bantering with us with a threatening sort of Spanglish and giving us the stink-eye. Senoras in floral dresses who hadn’t seen their husbands in years flirted with us and the younger girls giggled and ran and stared behind their schoolbooks. Negotiating a bus station in Central America can be interesting at the best of times, but this was in the middle of a chaotic armed struggle between a CIA-backed extreme right wing government and their masked death squads and an impoverished collective of leftist guerrillas whose figureheads were martyred priests. The smell of cordite in the air and the frenzied atmosphere on the street confirmed that getting out of dodge was definitely the best thing to do.

Grabbing a coffee at a sweaty joint at the terminus, we bumped into a Swiss journalist en route back to his bureau in Mexico City. This guy hipped us to the fact that there had been a big anti-government demonstration the day before, and that the militia opened up on the crowd. At least three Salvadorians were killed, as well as an Italian news cameraman. “It’s not cool to be a gringo round here at the moment,” he said. “You tend to arouse suspicion.” Chuckles may not have had the greatest sense of humour on the planet, but he spoke the righteous truth. The whole city felt on the edge of something. Every building – from the post office to Woolworth’s, was guarded by a heap of sandbags and men with M16s. Every male in the city, apart from us, seems to be packing. I spotted the driver of a tow-truck bending down to hitch an old beetle up to his rig. Down the back of his pants was a huge 9mm in chrome. Every bus had a crew of three a driver and two ‘assistants’ riding shotgun. Literally.

This was my first taste of a time and a place where life was in the balance, where the bread and butter realities of things were in constant flux, where one’s identity and affiliation weren’t about fads, fashion or taste, but a matter of life or death.

It was like the wild wild west with fully automatic weapons. But despite the arsenal on show, there was a real carnival atmosphere in the air, a fraught vibrancy that was addictive. This was my first taste of a time and a place where life was in the balance, where the bread and butter realities of things were in constant flux, where one’s identity and affiliation weren’t about fads, fashion or taste, but a matter of life or death. And I was going surfing here, where few brave souls would dare to tread! I was, shamefully, intoxicated by it all. Phil, on the other hand, was possessed of that curiously Welsh mentality of being unimpressed by anything. It was a good job one of us had his feet on the ground.

We finally found the right bus after running the gauntlet of shotgun-riders trying to drag us onto their vehicles. Once we’d played the familiar pantomime of haggling for the fare and feigning outrage at the price and telling the bus-hops to be careful with those boards hombre, we settled down into our hot steel chairs and held tight as the bus nosed out into the scorching afternoon. As we rattled into the suburbs avoiding potholes out on the highway that looked suspiciously like shell craters, through checkpoints, picking up folk and livestock on the way, the shotgun rider slings himself half out of the sliding door next to the driver, scanning the countryside with a dread expression. As soon as we left the city limits, a very non-Latin hush descended on the bus. Salvador is a tiny country and Libertad should only be an hour or so from the capital, but the journey seemed to take an eternity. The intensity of the silence was tangible. Every couple of kilometres or so was a machine gun emplacement, and every ten or so of these we are stopped. At at least three of these, the whole bus had to alight and the bus was searched. Each time this happened a brace of nervous looking combatants just out of their teens strapped to the max and wearing the regulation whispy ‘taches scan our IDs and ask us questions. Where are we going? Where are we from? Where do you stay? This begins to piss me off. An ancient farmer who’s been sitting next to me and smiling a gap-toothed grin at me since we left San Salvador picks up on my agitation. “Tranquilidad, hombre”, he whispers out of the side of his mouth, “Esto es muy peligroso” (this is very dangerous).

I can remember, though, the edginess of the few local kids who joined us in the water, paddling the caste-off thrusters of visiting Americanos held together by duct tape, and I remember this one wave, early in the morning just before our visas expired.

Apart from this one wave, all I can remember about La Libertad itself is a series of fragments. I can remember that Phil, with his passion for hollowness, was missing most of the time, malcontent and frustrated. I can remember stepping like a day old foal through the early initiations of surferhood, and found Punta Roca rights perfect and intimidating at the same time. The all-encompassing experience of the trip itself outweighed the intensity of the wave there. We’d had life-changing surf intensity in spades up in Oaxaca, but it was Libertad’s all pervasive daily rhythm that stayed with me. I’d wake at dawn and paddle out before breakfast with the Vietnam vet transplants from the Texas Gulf Coast, who served us pancakes and frijoles and eggs laced with fiery red chillies. I remember at the weekend that anyone in Salvador with a spare couple of bucks would come to town and rage all night in the bars and cantinas full of prostitutes. I can remember, though, the edginess of the few local kids who joined us in the water, paddling the caste-off thrusters of visiting Americanos held together by duct tape, and I remember this one wave, early in the morning just before our visas expired.

The take off was fast and steep. The only way to snag it was to paddle fast and straight and head to the trough of the wave before digging a long, drawn out bottom turn. When the curl caught up and the wall formed, I can remember burying the rail and rising again. Straightening my legs and shuffling back, the nose swung quickly round and everything was shimmering hues and bleeding colours and at the very moment I put my weight back on my front foot the sun burst out over the hills, and I can remember Libertad’s tumbledown skyline etched in relief against the half light as the speed and the whiff of ozone eclipsed everything. Charging to the bottom again, I pulled up into trim and the wall steepened and my rail buried deeper and faster and more critically. Now the bowl section approached and I looked to my right and saw the foam forming and I threw my arms up and my shoulders round to the left and my fins seemed to know what to do better than I. After this S-shaped turn, the wall reformed and I was flying in perfect stillness against the movement of the wave. I can remember the feeling of being fundamentally, beautifully alone there in the centre of the American continent knowing no one but the Welshman for a few thousand miles to each point of the compass. I remember in those few moments realising that this was how my life should be: loading the beautiful meaninglessness of riding a wave with my own significance because of the time, the place and the notion of where I was. I instinctively knew that I would store up these frozen moments and that I would return to them time and again and that they could never be taken from me. And there in that wave in El Salvador was something I would take with me forever and that it was good. That one meaningless wave meant everything to me. It was as much about finding the wave I had imagined on the other side of the world. All the madness it took to get to it intensified its lasting reality.

I remember in those few moments realising that this was how my life should be: loading the beautiful meaninglessness of riding a wave with my own significance because of the time, the place and the notion of where I was.

I paddled in soon after that wave, dragged Phil from his bed told him it was time to leave. We had ridden Punta Roca. Our time was up and there was nothing left to do. And I know I will ride that wave for the rest of my life.

Michael Fordham is the author of The Book of Surfing: The Killer Guide to Surf Culture