It’s easy to take an alternative lifetstyle for granted. But in Japan, for example, skateboarding is banned on the streets and tattoos are so upsetting to the establishment that if you visited a water park you’d be told to cover even the smallest inking up with a sticking plaster. But oases often spring up in the most unlikely places, and Posy Dixon had discovered such a one in the Love Hotel district of Tokyo and reported about it in our April/May issue in 2o12

Words by Posy Dixon, photography by Dan Medhurst

Having grown up in London in the nineties, and presently living in the East End in my twenties, I’ve always taken a certain degree of personal choice for granted in this grimy buzzing metropolis. From the age of 14 gigs at the Brixton Academy, crap tattoos, dodgy nose rings and vague attempts at skating have been the norm for my contemporaries and I, barely even ruffling the feathers of our Guardian-reading middle class parents. Similarly now, whether I ride a bike, ink my arms, shave my head or dress head to toe in purple spandex, no one really cares, freedom of choice and self expression is fairly loose. For youth in Japan however, the seemingly trivial choices in life, such as image, music, sports, can result in far more severe levels of social exclusion and disapproval, as displayed by the public park-wide tattoo bans and illegality of skating on the streets.

But every rule creates a rebel and a subculture, a group of people bold enough to break against the mould and create something positive through resisting the norm. This is the story of a group of people I was lucky enough to meet in Tokyo last year who had done exactly that.

But every rule creates a rebel and a subculture, a group of people bold enough to break against the mould and create something positive through resisting the norm. This is the story of a group of people I was lucky enough to meet in Tokyo last year who had done exactly that.

One of the infamous must-do experiences in Japan is to spend a night partying in Tokyo including a few hours «rest» in a Love Hotel. Love Hotels are basically motels that are conveniently available at an hourly rate – popular not only with unfaithful business men and prostitutes, but also more innocently by young couples too respectful to get it on in the family home, or the occasional drunk husband too wobbly to face domesticity. These establishments are conglomerated in the Shibuya and Kabukicho districts of Tokyo, often boasting themed rooms, vending machines and badly-worded British signposts, providing endless entertainment to Western tourists.

It was in the Love Hotel district that I ended up last summer, armed with a scribbled map from a local friend, directing me though a maze of seedy buildings and Korean restaurants to a multicoloured graffiti-skinned building known as “The Ghetto”, an island in a sea of bargain-bin romance.

The Ghetto, until only three years ago, was a Love Hotel itself, owned by the Ohashi family who had run the joint for several decades, offering the usual service of by-the-hour respite to visitors to the district. That was until Grandma Ohashi passed away and her children were considering shutting it down and selling the business on. Enter young grandson Akihiko (known by all as Ako) skater, guitarist and graffiti artist who had a vision of an oasis of underground culture where the music, sport and art that he thrived upon had a safe and welcoming place to breed within in the city.

Upon entering the venue the first thing you’ll stumble upon is the indoor mini ramp in the lobby, possibly the only mini ramp I’ve ever seen that has a pole sticking straight through the middle of it and what is clearly a household doorway as an entrance. Despite its quirks the ramp is perfectly constructed with smooth even transitions and enough head room to accommodate most Japanese-sized skaters.

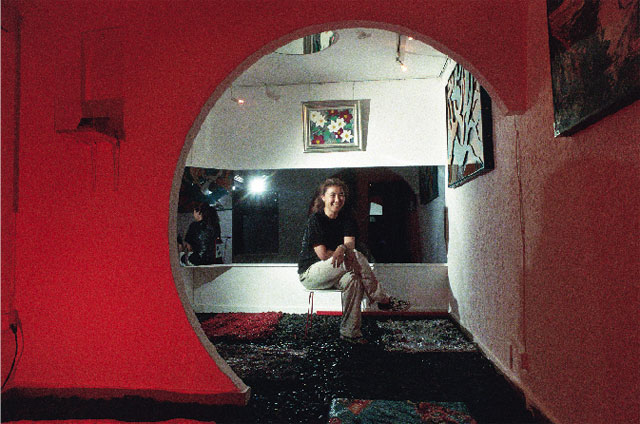

Through the next room you find a bar and live music venue lovingly named Hell’s Kitchen. Here Ako and his team of barmaids host gigs, spoken word nights and parties, as well as serving cold beers to thirsty skaters throughout the afternoon. Venture upstairs and the building’s past life becomes even more glaringly obvious as you discover an array of bedrooms, complete with circular doorways, mirrored ceilings and even more abstract mid-room poles. These spaces are now occupied by a trove of DIY art galleries and shops, rented out at low prices by Ako, selling everything from second hand records and skate decks to clothes and books about tattooing and body modification.

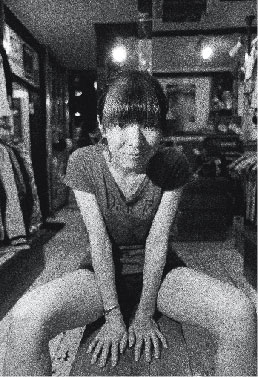

After a wander through the shops chatting to various welcoming patrons, we head downstairs to investigate the chances of having a skate. The mini is now managed by Kyoko, mother of a local skate hero, who two years previously wanted to help the facility where her son spent so much of his time. Her aim was to help run the ramp as a place where the experts could improve but also where beginners could learn away from the skate-banned sidewalks. She now runs a cheap beginners session every afternoon and rents out pads and boards to any skate idiot (including me) who fancies a session. Kyoko explains to us how it’s unusual to find skater girls in the city, or women involved in such a place as the Ghetto – but the liberal and forward thinking mentality of the centre has attracted many girls who express interest in alternative cultures such as tattooing, skate and graffiti art. Hence the tattooed girls working the bar and shop upstairs, and the crew of girls happily shredding the ramp together.

It may seem normal to us to find a ramp in the city full of tattooed skaters, but ink in Japan is a major taboo, commonly associated with the Triad, gangs and other violent subcultures. We learn this first hand when we visit a water park outside the city and are made to hide small tattoos with a plaster. So yes, these girls are putting themselves out there, and the Ghetto provides a small community that welcomes them with open arms. Chatting to the barmaids they explain that although tattooing is slowly becoming more accepted to have full sleeve will certainly prevent you from working in most mainstream establishments (such as restaurants, offices and shops) and many elders would not even talk to you in response.

After a wobbly skate session we share a beer with Ghetto owner Ako and have to stifle laughter when he solemnly tells us how the Ghetto was inspired by a scene in Vin Diesel’s Triple X. What’s weird is that to us, a group of friends visiting from London where tattoos, warehouse parties and skating are commonplace, the Ghetto almost looks like a cheesy «fake» themed skate/rock bar. The reality is that this creation is the result of a group of Japanese friends, inspired by the American stereotypes seen on TV and silver screen, who have taken the motivation and hard work to bring these movie fantasies to life.

Ako promises that if the Ghetto ever becomes overpopulated or busy he is going to shut it down, as he doesn’t want it to become susceptible to the usual rules and regulations that shape the city. Go visit before it happens, the Ghetto – one of the most welcoming, well organised and functional bits of social rebellion you’ll ever see. Get down there, hang out, meet the family and have a skate (though mind the pole). Explore the maze of shops upstairs and feel lucky to have stumbled upon one of Tokyo’s best kept secrets.

Facts

Getting there: You can walk to the Ghetto from Shin Okubo Station

Address: 1-1-1- Nyakunin-cho Shinjuku-ku

theghettotokyo.com

The Ghetto is closed on Mondays