90s VHS? Nah, this is just how Palace edits look now.

Action sports have a reputation for being progressive. They’re innovative sports by their nature, and tend to be associated with a liberal, forward-thinking demographic. And not just in terms of those people wanting to legalise weed.

But it’s hard to ignore that skate brands are now, incessantly, looking back to the 90s. From t-shirts that could have been worn by Big Will in the Fresh Prince, to the fact that the most recent issue of Sidewalk has a cover that could have been popular in 1994 never mind 2014, everyone is using the aesthetics (but thankfully not the equipment) of 90s skateboarding culture. And, sartorially at least, snowboarding and surfing brands are also jumping on the (grunge)band wagon.

Obviously this is a wider societal trend that has become apparent in music and fashion, but for a sector that has always marched to the beat of its own drum, it’s jarring to be forced to look at skateboarding as another fashion industry. And yes… I know that this has been true all along. Skateboarding is a commercial endeavour for many, and capitalises on trends. But does the 90s nostalgia thing mean we’ve hit a dead end? Will skateboarding never have its own unique aesthetic again because all the other options have been exhausted, and nostalgia is all that’s left? And how the f**k, in all of this, does nostalgia actually work?

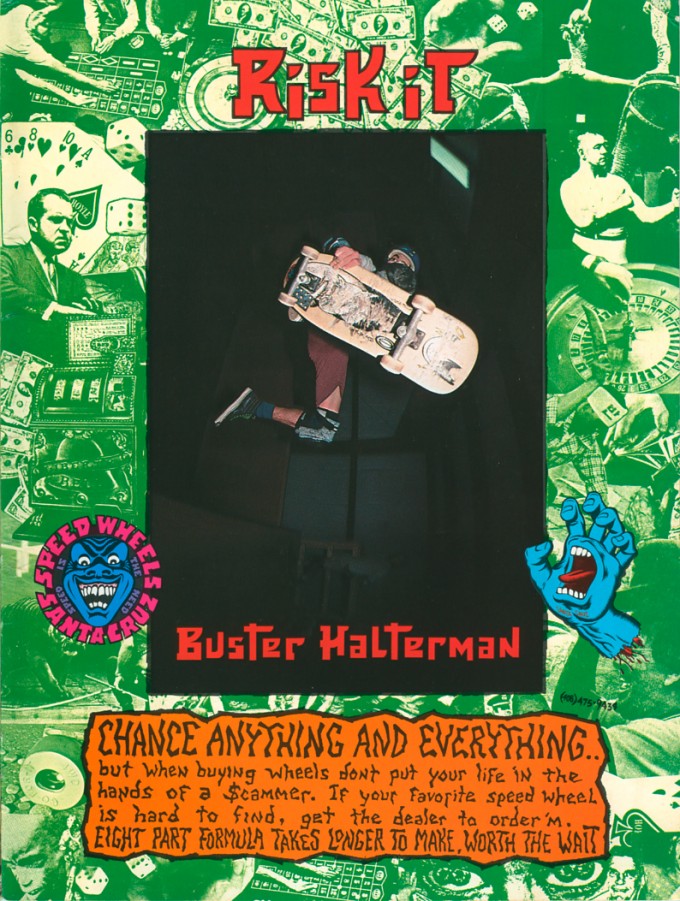

Santa Cruz Speedwheels Ad, 1990, via daVsen

Using nostalgia as a marketing strategy is by no means new. Brands know that evoking a time when their target market were in their teens and twenties, means that customers get zapped with a hella emotional pull in the direction of that product. There’s even a name for the fact that stuff we experienced when young maintains its vividness within our memories as we get older – it’s called the reminiscence bump. This occurs from the age of 10 to 30, but peaks in our early twenties. This creates a nice ‘bump’ on the graph of what we recollect most clearly in our lives (or the lifespan retrieval curve, if you wanna get technical).

But wait a minute. Why am I being sold stuff in 90s packaging when I’m in my early twenties now? Yes, there’s a market of mums and dads for skateboarding stuff. But really, I’m the person a brand wants to attract because I have an amount of societal kudos just for being the age I am. I also have few responsibilities and just enough expendable cash to make me profitable. I’ve no kids that need fed. I’m the primary market for a skateboard brand to target (…aside from my ownership of a vulva. But that’s for another day).

Perhaps the reason this kind of advertising works is due to the cascading reminiscence bump instead? That’s the theory that you can feel nostalgia for a time you didn’t live through. Sounds good. But actually, the research points to people feeling a nostalgia for the music of their parent’s adolescence, because their ‘rents played it during their own reminiscence bump. See the cyclical nature of this stuff? But that still doesn’t explain why I’m so damn drawn to grunge typography over monochrome skating images. My Mum didn’t force a love of bad graphic design on me.

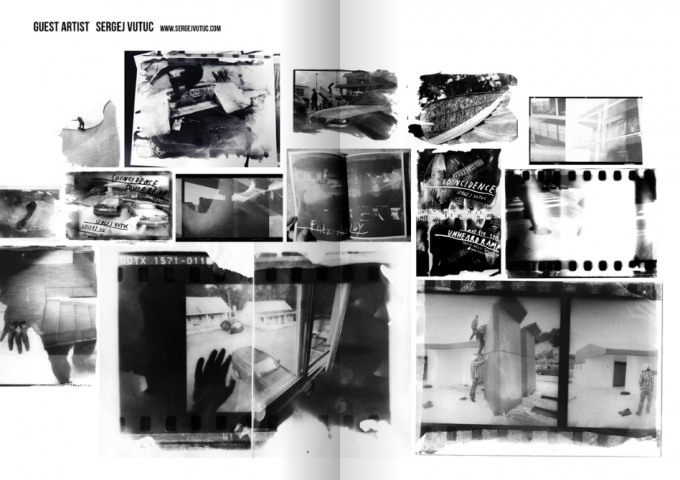

Vintage or new? It’s… new. Via Science‘s 2014 product book

As someone who was born in 1991, I’m too young to really remember anything that happened in the 90s aside from when Princess Diana’s died. But I still have a sense of how it felt to be alive then because I watched Live & Kicking.

Because I was too young to consume culture – pop or counter – at the time, I want to engage with it now that I have coins in my pocket and a somewhat ‘real’ job. I desire to know what I missed when the 90s were at their peak, when my mum wouldn’t let me buy the Spice Girls video that I wanted and I had to be content with my remote-control Tony Hawk shreddin’ the kerb instead of me.

Maybe for smaller, independent brands, the 90s nostalgia in their materials is a genuine tribute by the owners and creators within that company to a time when skating felt different and exciting for them. Or perhaps the skateboarding universe is just over-excited about coming of age as a sport in general, and that it can finally utilise nostalgia. But for the big guys, who spend all their time and money trying to work out what ‘the kids’ will love, the only conclusion that I can draw is that this 90s renaissance in skating isn’t anything to do with nostalgia. Not really. It’s about FOMO. The ultimate FOMO.

Sims Staab Ad, 1990, via daVsen

If you missed that amazing gig, you can still buy the band t-shirt and show it off on Instagram. If you missed your friend’s birthday drinks, you get stressed out, but the world will be set to right when it’s your birthday and you get to post stories of debauchery yourself. But the early 90s? Sorry, you were busy being breast-fed. The only way you’ll ever manage to make yourself feel better about missing out on that is by purchasing these products. Dolla dolla bill y’all (Wu Tang – 1994).

And this sense that you missed out on the best of times is only compounded by the fact that the people who did live through the 90s are a bit rose-tinted about the whole decade. Designers and photographers have cherry-picked all the best aspects of the time for its re-appropriation, and have conveniently forgotten to mention that actually, skating in the 90s sorta sucked.

What brands are missing is that the best thing about skating now is that it’s less insular and cliquey than it’s ever been. You don’t have to wear a certain thing or be a particular way to be accepted. You may get a dirty look from a member of the god-fearing general public, but skaters are now an encouraging clan, keen to embrace all who wish to be involved. And sure, we’re kicking ourselves that we never got to wear a pair of those sweet gigantic jeans, but we don’t miss the tribalism that once seemed so inherent within the sport. As long as the 90s revival only extends to a marketing ploy, you can capitalise on my FOMO all day long. Even if it is a little depressing.