“Oh my god, look at him!” Inside the open-topped Land Rover, everyone is jostling to get a better view. We’re all talking at once, but in excitable whispers – as if we’re terrified that anything louder than a camera shutter will anger or scare away the king of beasts.

Less than two metres away from us, the adult male lion couldn’t care less. In fact, he looks positively bored, yawning and rolling onto his back with his paws in the air. After about five minutes he gets up, shakes his magnificent mane out, and squats down in the bushes for a poo.

“You see,” says Craig, our guide on this trip round South Africa’s Addo National Park, “he doesn’t even care that we’re here. To him the vehicle is just this funny animal that shows up every now and then but doesn’t do anything.” This, Craig explains is because the animal posing so obligingly for us is a “wild” lion.

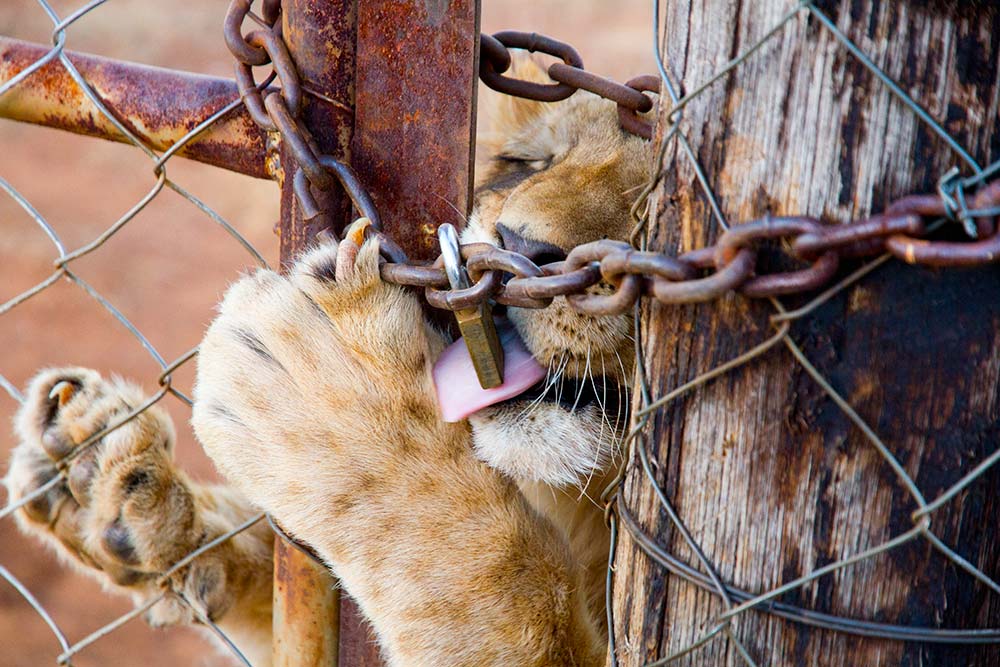

“Guys will literally walk up to a caged pen, like a kennel, put a rifle through and shoot an animal on the other side. It’s horrific stuff.”